Recreating a fading Makar Sankranti tradition from East Bengal and Assam.

We attempted, in a limited way, to recreate a fading tradition from my childhood on the balcony of our 12th floor apartment in Greater Noida West.

Six-year-old Googool (Advay) spent the previous night creating his own version of a Mera-Merir ghor using cut and stapled pieces from discarded carboard boxes which he then painted in multiple colours.

Woke him up early for the ritualistic burning of the Mera Merir ghor on Makar Sankranti morning. He was a bit apprehensive about the pollution we would cause. The explanation that the house was a very small in size and will not contribute much to the toxic air assured his little troubled mind. But he still has to come to terms with the idea of burning down something lovingly created.

As the little cardboard house went up in flames, we chanted that old silly song:

Mera-Merir ghor jole re hoi!

Mera gelo bajaro, Meri gelo koi?

Mera-Merir ghor jole re hoi!

(The ram and ewe’s home is up in flames!

The ram’s out shopping and the ewe’s missing.

The ram and ewe’s home is up in flames!)

The little rising flames took me back on a memory trip to my childhood in faraway Shillong.

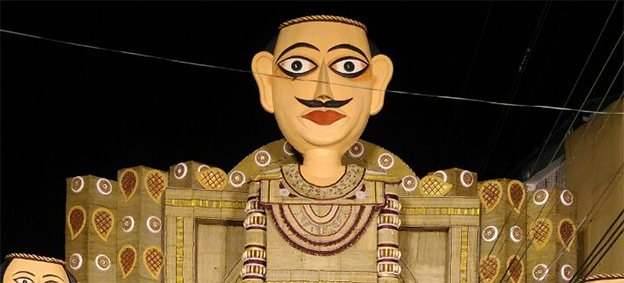

A burning cardboard Mera-Meri house on a 12th floor balcony (Image: Varsha Choudhury)

Every Makar Sankranti (Poush Sankranti in the place I come from), a loud chorus of young voices yelling out Mera-Merir ghor jole re… rang the dawn sky above the din of bursting bamboo burning in the fire.

While I am unaware of the intended meaning behind this announcement of the burning down of the sheep family home, but I was a very active participant in the culmination of a ritual that began quite a few days in advance.

Have found very little online references to this Sankranti ritual usually practised by children in the districts of Sylhet and Mymensingh of the erstwhile undivided Assam and East Bengal (now Bangladesh), in Assam’s Barak Valley, Tripura, and in other parts of North East India with sizeable numbers of migrants from East Bengal (such as Shillong, my hometown).

A similar ritual, ‘Meji’ is also practised by the Assamese during Bhogali Bihu.

Makar Sankranti is a harvest festival in many parts of India and is celebrated in a number of ways. Only that we Sylhetis (part of the larger flock sometimes referred to as Bangals – migrants from East Bengal and undivided Assam) didn’t take as much enthusiasm in flying kites on that day (as in many parts of the country) as we enjoyed burning houses (believed to belong to a sheep couple).

After the harvest there is a lot of straw around and the eastern parts of our country is also rich in bamboo. These are the best ingredients to build a house that will burn down with a lot of light and quite a bit of noise. Perfect for a chilly winter morning and to welcome in the spring.

Children in the neighbourhood would form their own groups to collect the straw and bamboo to erect their thatched huts in time for the Sankranti eve.

As I (and my friends) grew up in the hill city of Shillong, bamboo was in abundance but not straw. Being the ingenious people (that we still are) we bunched up the dried needle-like pine leaves of the Khasi pine trees (Pinus kesiya). These were painstakingly collected in jute bags using rakes from the slopes of the neighbourhood graveyards (yes, graveyards).

We would then cut open large baskets used to transport tez patta (bay leaves) and tie them to a bamboo frame to form the base of the walls and the roof. And in the large holes of the baskets we stuffed in bunches of pine leaves.

The structures were usually simple and single-storied. However, some of the more adventurous ones (with more helpful grownups) put up two-storied structures with fancier architecture.

This construction process usually took a good few days. Especially for us, as raw material wasn’t always easily available. It helped that we had a long winter vacation (often stretching from late November to early March) in Shillong schools.

There was sometimes bitter competition between different groups and often there would be attempts by rivals to burn down the competition’s Mera-Meri houses well before the Sankranti dawn. Therefore, the entire team had to be on guard all night long.

Once a few from our group were caught by people during a botched attempt to burn down a rival Meri-Meri house and had to spend a good part of an hour being tied to a tree trunk before the grownups came to the rescue.

But guarding was more of an excuse. The real intention was to party.

This was perhaps the only time of the year (except for during Durga Puja) when children were allowed to be out all night long. The cooking was usually taken care of by the mothers. But we all pooled in money and did the shopping.

The menu invariably included mutton and we all sat down around the bonfire eating and singing happy songs, in different languages with our own twists to it. Some favourites included: Picnic party bhoilo, aata ruti khailo; Bambai se aaya mera dost, dost ko salaam karo. Raat ko khaao peeyo, din ko lakdi kaato…

This was also the time when many a young kid amongst us got introduced to smoking. Not cigarettes but dried up Chayote squash vines cut into small lengths. For some, it was only a once-in-a-year experience, but for a few it was the beginning of a life-long habit that would take a toll on their health and more. The idea of alcohol was, thankfully, still many years away from our impressionable minds (however, my brother, who is elder to me by a few years, informs that there was very possibly alcohol involved, as he remembers the clinking of glasses).

The fire, strong Assam tea, and dancing, kept us warm in the chilly Shillong winter night. The younger ones would fall asleep soon after midnight and would be taken home asleep by their fathers.

Our fathers would keep an eye on us but from a distance. Letting us bask in a feeling of independence around a house that we built ourselves.

For those who managed to keep awake through the night would wake up the others much before dawn. It was time for a ritual bath. In the plains down below, where it was warmer and houses had ponds, the kids would race each other to be the first to dive into one.

Up in the hills, we had no such luxuries. A bucket of hot water and a bar of soap welcomed us to the cold and dark bathrooms. A quick bath later, we were all set for the fire ceremony.

Everyone, the young and old, stood around the Mera-Meri house along with pitha (specially prepared home-made sweets made of rice flour or in some cases pulses along with the obligatory tiler naru (sesame seed laddoos) and batashas and kodmas. We threw a few as an offering to the fire god before commencing on a day of pitha feasting (sweets were however not the main dish. That, for a Bangali, is always fish.)

Then someone set the house of fire and the chirping of the birds would be drowned by the crackling of the fire (and firecrackers thrown in for good measure), punctuated with bursting bamboo and chants of “Mera-Merir ghor jole re hooooi!”

Three decades later I chant that familiar chant with only Googool and Varsha (my wife) for company, only that now it is against the background sound of burning cardboard.

(An earlier version of this post was first published in 2016 on IBNLive.com – which is now News18.com)

One comment

'Mera-Merir ghor jole re...' on an apartment balcony in western Uttar Pradesh